Mark Kermode once stated that anyone who said they’d guessed the ending of The Usual Suspects was lying. I have never quite forgiven him for this – I guessed it, but what proof do I have? Essentially he was out there calling me a liar and I had no redress.

However, I am willing to let bygones be bygones, at least to the extent of attending a showing of Theatre Of Blood that followed a panel discussion – chaired by Kermode – on the fate of the professional critic in the internet age, when a movie poster can be adorned by the ravings of the general public via Twitter and nobody seems to care that, say, Derek Malcolm only gave the film two stars.

The panel consisted of six professional critics (including MK), many of whom weren’t keen on the term ‘professional’ – or the term ‘critic’, for that matter (perhaps Kermode’s choice of film had made them nervous). I can’t remember much of what else they said but it was all very amusing and interesting, and I finally forgave Kermode for calling me a liar when he concluded that some of the best writing on film was on the internet, and that some of the people perpetrating it were in that very room (Screen One at the ICA). ‘You know who you are’, he said.

It’s unlikely that he meant me, considering that, according to the stats, only two people in Brazil have even looked at this site. But I can pretend. Criticism – this was a point that got made – is after all a kind of performance, and its relation to the truth therefore not wholly straightforward.

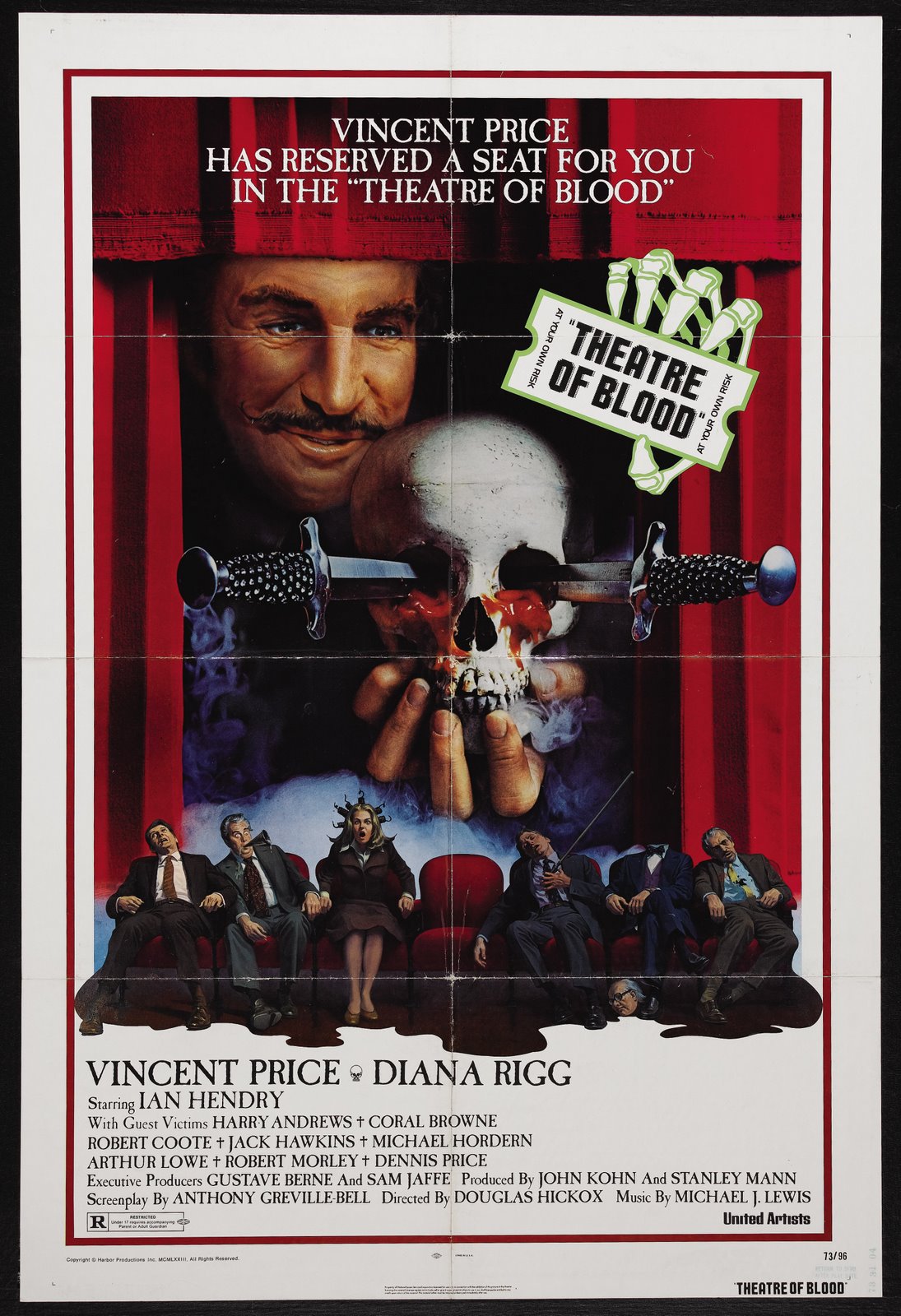

But we weren’t there to praise critics, we were there (or at least I was) to see them stabbed, decapitated and electrocuted, among other things. In Theatre Of Blood Vincent Price is Edward Lionheart, a hammy Shakespearian actor who, on failing to get the much-coveted (by him, at any rate) Critics Circle Award, hurls himself into the Thames, from whose mud he is dragged by a bunch of meths-drinkers, whose king he, essentially, becomes. With their help, and that of his daughter (Diana Rigg) he sets about killing off the critics who have savaged him over the years, using methods loosely adapted from the Bard’s work.

So critic Trevor Dickman (Harry Andrews) is co-opted into a fresh take on The Merchant of Venice in which Shylock does get his pound of flesh (‘Living theatre yes – but isn’t this going a bit far?’, he frets, as Diana Rigg tells him that their revisions will include ‘one large cut’). This flesh is sent to the head of the Critics Circle, Peregrine Devlin (Ian Hendry), along with a note apologising for Dickman’s absence (‘…but my heart is with you’). There are a lot of jokes, mostly good ones, in Anthony Greville-Bell’s clever screenplay and director Douglas Hickox offsets camp theatricality with visceral thrills and a sense of genuine menace. Given a license to chew the scenery, Price unsurprisingly rises to the occasion, while a cast of stalwarts including Arthur Lowe, Dennis Price, Jack Hawkins and Diana Dors (the latter two becoming an unlikely Othello and Desdemona) give impressive support. There is also a surprising amount of gore – this is a horror film where the characters tend to be react not by screaming, but by grimacing and going ‘Euuugh’.

‘Only Lionheart would have the temerity to rewrite Shakespeare’, is Devlin’s dry comment on that pound of flesh he has to unwrap – which brings up an interesting point. Lionheart’s performances are slated for being too traditional – he despises modern ‘mumbling’ – and yet his murders rank as some of the most audacious restagings of Shakespeare in the modern age. In Titus Andronicus, Tamora Queen of the Goths inadvertently eats her children baked in a pie – here this is reimagined as a TV cookery show (‘This Is Your Dish’), with Robert Morley cast as the Queen of the Goths and the children replaced by his pet poodles. Meanwhile the death of Joan of Arc (Henry VI Part One) becomes electrocution by hair dryer (Vincent Price’s wife-to-be, Coral Browne plays Joan to Price’s camp hairdresser).

Even as he overtly espouses tradition, Lionheart is in fact a brutal moderniser – a bit like Mrs. Thatcher (herself something of a one-note performance). And yet he remains conservative at heart – all he really wants is the recognition of the critical elite. And so, to return to Mark Kermode’s original question (he had fled the auditorium by now, I believe) the tendency of the film is actually to reinforce the authority of critics – albeit by killing them.

Despite which, Lionheart seems to have inadvertently ushered in a new age in which the performer connects directly with his or her audience, just like on Twitter, and even enlists their help (I believe this is now called ‘crowdsourcing’). Of course in this case the audience are barely-articulate, meths-addled vagrants. But we probably shouldn’t worry about that.

Recent Comments