Normally I unearth the cultural artefacts that interest me by dint of patient digging in obscure corners, but sometimes something comes barrelling out of the internet during an idle hour to catch me off guard rather like MMA fighter Andrei ‘The Pitbull’ Arlovski keeps doing to the hero of this film.

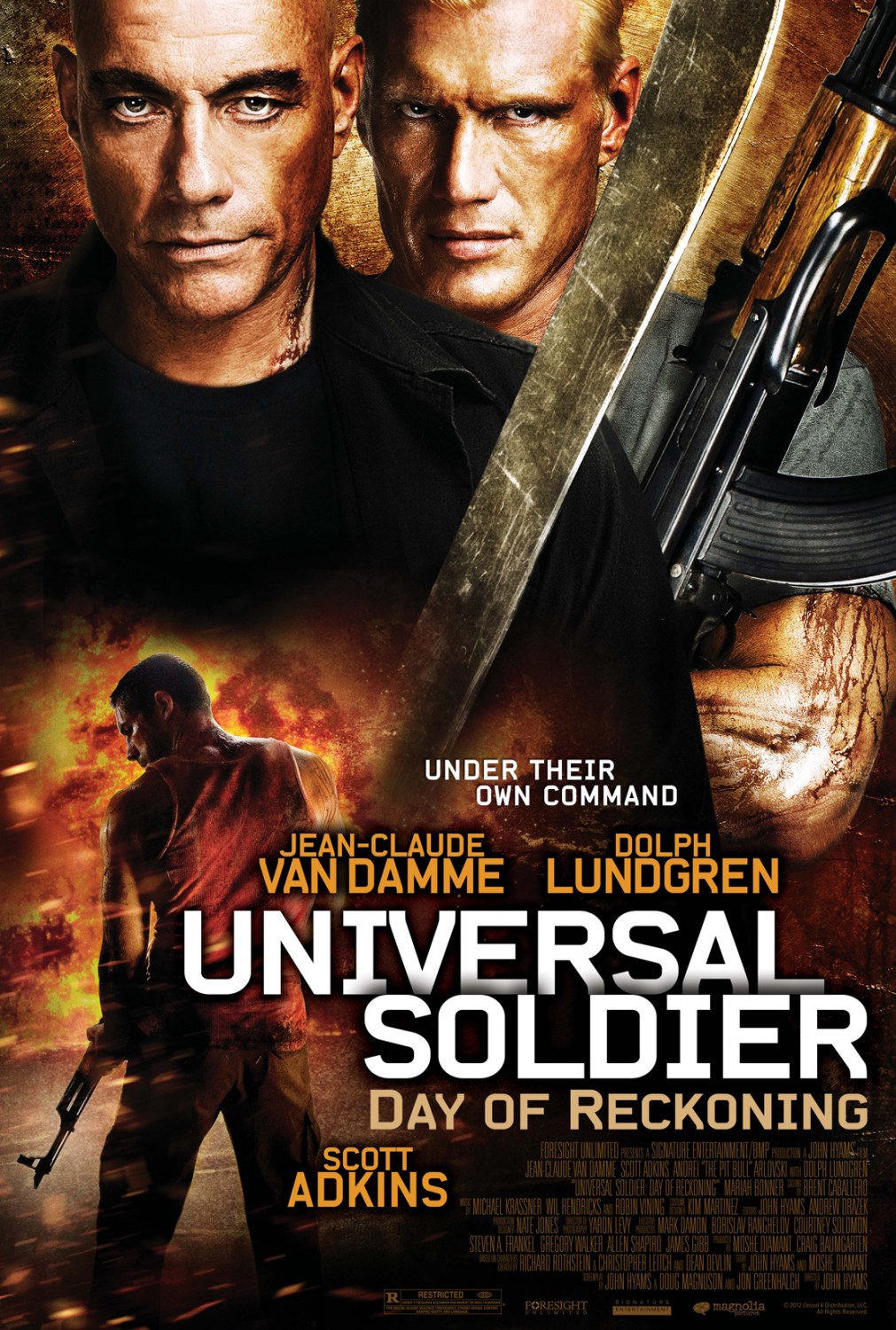

When I first read on Tumblr that the fourth Universal Soldier movie had been favourably compared to the work of Werner Herzog, David Lynch and Gaspar Noe. I thought: this is a joke. Then I bought the DVD – I like a good joke. (And it was only £5 in Fopp).

But it was all true, sort of. And I hadn’t even been drinking when I saw it (as I remember).

USDOR begins with a first person POV from the perspective of the hero, John (Scott Adkins) as he watches his wife and young daughter brutally murdered by intruders led by Jean Claude Van Damme (playing Luke Deveraux, previously a ‘good’ character in this series). Now when Gaspar Noe, throughout Enter The Void, uses this first-person POV technique the effect is to emphasise the vividness of lived (or after-lived) experience. Here we know from the off that something is not quite right: director John Hyams somehow makes us understand that we can’t believe Scott Adkins’ eyes. The impression is confirmed when we learn that John may never have had a wife and child – the murder is (possibly) a memory implanted by government scientists who want to encourage him to hunt down Deveraux.

So already what we have here is a neat deconstruction of the revenge-driven action movie. Aren’t the hero’s loved ones in such films only there to get murdered and justify the violence to follow? Whether they ‘really exist’ or not is a question well worth asking.

An especially brave aspect of this deconstruction is that it takes place in a context in which there hasn’t been much construction in the first place. Our hero is an amnesiac with little recollection of his previous life, and no certainty over whether what he seems to remember is genuine. And we are as much in the dark as he is.

And when I say ‘we’ I definitely mean me. I haven’t seen any of the other films, except maybe I saw the first one, I can’t quite remember. Which means I can really identify with John’s hazy memories. Even my idea of what a UniSol is is a bit vague, though I seem to understand that it is a cyborg made out of a dead soldier. Which certainly makes it the perfect subject for a sequel – indeed, endless sequels.

In this particular sequel there is a rogue cell of UniSols who are plotting to take over the government, maybe even the world, and they are led by JCVD and Dolph Lundgren, as Andrew Scott, another returning character. Meanwhile, government agents try and stop them, using programmed UniSols, which are then reprogrammed by JCVD – or converted even, since his organisation is a sort of ultraviolent ‘church’. It is soon very hard to tell the ‘good guys’ from the ‘bad guys’, creating the kind of murk that’s highly appropriate to a distant sequel in which events are far removed from the (comparatively) fine detail of the original. It’s entropy in action.

But there is action. Savage fights involving the aforementioned Arlovski and our John erupt out of nowhere with surreal intensity. This is still a movie that does what it says on the tin – it’s just that the tin is empty.

And this emptiness is its defining quality. In between the action sequences, something of the eerie stiltedness of David Lynch creeps into the scenes of John investigating his own past. But whereas Lynch’s work evokes the shadowy depths of the subconscious, Hyams brings to mind computer games: puppet-like characters delivering banal phrases with a bizarre kind of portentousness – as if any one phrase might hold the key that unlocks the scenario in which they are trapped.

The plot turns on such hackneyed tropes as a nightclub matchbook left beside a corpse as a prompt to the hero’s next move. The imagery shamelessly steals from The Shining and Apocalypse Now. And Arlovski plays an agent codenamed ‘the Plumber’ who really is a plumber, and is activated into becoming a killing machine while lying under some woman’s sink.

All these strike me as rather good deadpan jokes that also suggest the void at the heart of the film. Here’s another:

Hitching up with a lapdancer, John comes across another identical version of himself hiding out in an abandoned building – imagine his dismay when the lapdancer, who has been rather frosty with him, immediately embraces his double. It’s as if poor John may not be the hero of his own story, but rather his own inferior sequel.

And when I say ‘imagine his dismay’, that’s because you have to – certainly, Scott Adkins does a creditable job of playing a human blank, but he is less adept at emotions. For example, conveying the agony of having a hole drilled into his skull without anaesthetic is clearly out of his range. I can’t fault his martial arts though. I don’t know enough about them.

In this context JCVD and Lundgren are practically grand old thespians, like Richardson and Gielgud, but they don’t get a great deal of screen time. Nevertheless, JCVD’s death scene achieves real heights of mystical intensity. I repeat: I had not been drinking.

In the end John decides that it doesn’t matter whether his memories are false or not, he’s keeping them anyway. Then, having killed JCVD, he becomes the leader of the rogue UniSols. Does this make any sense? I’m not sure. Does it matter? No. The less there is to it, the more the film works.

We are left with John’s memory of him pushing his daughter, who probably never existed, on a swing that never existed either, in a garden that – well, you get the idea. There’s something haunting about this: the emptiness of the tin resonates. The film even lends the word UniSol a poignant quality suggestive of both existential aloneness and the possibility of a soul, a ghost in the machine.

So maybe I had had a glass of wine. That isn’t the point. Neither does it matter that John Hyams also directed the previous sequel, which has not had such grand claims made for it. (I suppose I should see it, but I suspect that wine will definitely be needed there.) This is a better film than anyone had any right to expect – a film that uses its gliding camera moves and visceral-yet-mechanical outbursts of violence to draw us smoothly into a chill, aching absence. It’s as if a séance had been conducted around an action movie – daring to interrogate the clenched masks of the muscled-up men and ask: ‘Is there anybody there?’ Only to receive, eventually, and so softly that you might have imagined it, the melancholy reply:

‘No.’

Recent Comments